A Conversation with Nir Hod: Dorian’s Gardens

By NOAH BECKER, December 24nd, 2025

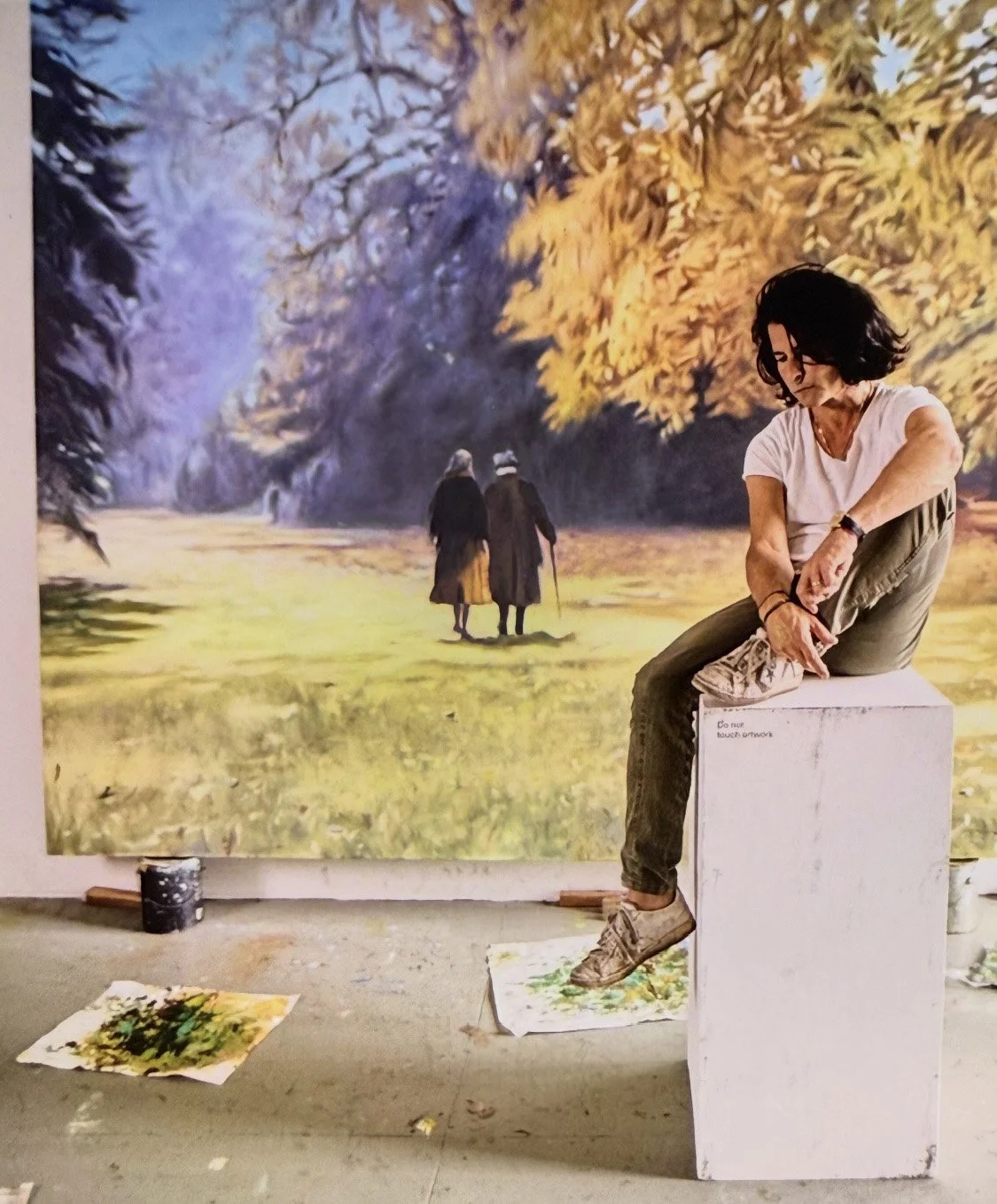

Nir Hod’s latest series, Dorian’s Gardens, on view in Los Angeles at Michael Kohn Gallery merges memory, nature, and art history into immersive, dreamlike landscapes. Across paintings and sculpture, Hod navigates the tension between beauty and decay, exploring themes of transformation, desire, and the passage of time. In this interview, he shares the inspirations, processes, and emotional frameworks behind his work, from reflective chrome surfaces to layered narratives and the quiet landscapes that have shaped his vision.

Noah Becker: Dorian’s Gardens is a reference to Dorian Gray. How did you arrive at this theme?

Nir Hod: In recent years I have referred to these paintings by a name that grew out of a personal experience, and also out of something experimental. During the COVID period, for the first time in my life, I lived in nature on the shore of a lake in Connecticut. It was a time of observation, quiet, and a new realization: one hundred years are not enough to truly enjoy, to deeply appreciate, and to contain the beauty and joy of simply being alive. From this understanding the title “One Hundred Years Is Not Enough” was born.

Over the past two years, the works have evolved and deepened. They began to engage with memory, with a certain sense of loneliness, and at the same time with the seduction of beauty in a world that is sometimes quiet, sometimes painful, yet always captivating. The paintings became more psychological, more inward.

All of my bodies of work deal with a twist, a transformation, or a shift of something iconic, historical, and familiar. Over the years, my work has often been discussed in relation to The Picture of Dorian Gray by Oscar Wilde. One day, while painting, a thought occurred to me: if the story of Dorian Gray were translated into landscapes or nature paintings, what would they look like? What kinds of flowers would appear in them, and what kind of feeling would these paintings create?

Almost naturally, the title “Dorian’s Gardens” gave the series an additional narrative, a sense of reference and history. Much like external forces that influence our personality and behavior, so too here—a concept, an image, or a story becomes embedded in the work and transforms it. At times, we live and change out of an image that emerges within us, and from it we continue to shape who we are.

The works are very painterly, not photo-realism but still realer-than-real. They have an almost Ab-Ex quality at times. Is there a hidden narrative in these paintings?

First and foremost, I see myself as a storyteller rather than a painter, so there is always a narrative. The narrative in my work develops and changes, shaped by shifting sources of inspiration, moving toward an emotional rather than a descriptive place. This is nature as we feel it, not as it looks. The flowers are self-portraits some alive, some broken and withered. They are my feelings, my longings, my loves, and my disappointments.

The works are far from photo-realism, a style that does not speak to me at all. I believe realism and abstraction are one and the same; it depends on the degree to which we use each of them. The paintings exist in a zone of imagined tension, and therefore contain something more real precisely because they are imaginary. They are the reality we create in our imagination.

The narrative in all my works is similar: it deals with pain, memory, transformation, and desire—something that is deeply seductive yet equally disturbing, a sense of time turning while our eyes are still fixed on it.

Becker: Why is the tension between beauty and decay so central to your practice?

This is who I am, and that is why I am so deeply drawn to themes of contrast and conflict. I believe that if you are a sensitive, reflective, and self-aware person, it is impossible not to engage with these tensions and feel them. The privilege of being an artist or a creator lies in the fact that in art unlike in life this dynamic works with great precision: the meeting point between death and beauty. In art, it is possible because it is imagined, because it allows space.

These are the songs that shaped me, the films that etched themselves into my heart and formed my emotional and aesthetic mechanisms, and the Old Masters’ paintings that led me to paint. I believe this is an energy that emerges and enables us to truly understand beauty through pain, or pain as it reveals itself within beauty.

For this reason, the titles of my bodies of work often deal with interpretations of time, memory, loss, and heartbreak. Titles such as Once Everything Was Much Better, Even in the Future, The Night You Left, The Life We Left Behind, 100 Years Is Not Enough.

Even the word pain is embedded within the word painting.

It simply works together in a way that feels profoundly right. I value the fact that art allows us to understand life more deeply rather than the other way around. This is a central theme in my practice. These are the foundations of art and of humanity at its best.

Becker: What draws you to water as a recurring subject?

It happened organically. At a certain point, as I was looking at the first series of paintings I created using chrome, I realized that some of the works resembled frozen landscapes abandoned lakes and swamps. I noticed that in some paintings I was depicting landscapes containing water, while in others there was an effect reminiscent of William Turner, though in a completely different way. Gradually, the paintings began to resemble damaged daguerreotype photographs of still life wounded, almost archival images.

One day in the studio, green paint accidentally splashed onto one of the paintings. At first, I was frustrated, convinced I had ruined the work. But the more I looked at it and especially the following morning it began to resemble something that looks like remain of vegetation floating on the surface of water. It was an extraordinary effect of water, unlike anything I had ever seen before in a painting on canvas. It felt like becoming a kind of victim to the talent of something I had created myself.

From that moment on, the technique opened up. A process emerged in which the surfaces appear like dirty water of swamps and lakes through the use of acid and other toxic materials that simply froze onto the canvas.

Becker: Tell me more about your use of reflective chrome paint? More about the process and what draws you to this contrasting surface.

My use of chrome began completely by accident, while I was working with Paul Kasmin on a sculpture of a genius child. We were looking for alternative materials to bronze, and that is how I was exposed to the chrome process a process that we developed and deepened over several years, to where it is today. It is a demanding process that requires a specific studio and certain conditions.

During the work, I am destroying the chrome layer on the canvas and removing parts of it in a very aggressive process and way, in order to expose the painting on the canvas beneath it. In this way, three paintings exist simultaneously within one painting: the initial painting on the canvas, then the chrome painting that is placed over the oil painting, and finally the third painting created on top of the chrome which integrates with the painting beneath it and with the chrome itself. These are three different painted layers that complete one another and converge into a single work.

I use patina and additional materials to create flaws, depths, and effects that recall the way time and history are present in sculpture and painting. When the chrome is absorbed into the paint, a reflection is created, and the painting undergoes a process of transformation from abstract to figurative. The viewer is drawn into the painting, reflected within it, and a very strong psychological relationship is created between the painting and the viewer. You are no longer just looking at the work you are involved in it, you are part of it.

I am fascinated by this material because it embodies the contradictions that occupy me: there is something deeply nostalgic about it, and at the same time futuristic, almost metaphorical.

Becker: What role does art history play in Dorian’s Gardens?

History is a central and essential component of my art. In fact, all of my work is an observation of history through a different prism with a profound twist on what we are accustomed to recognizing as history. I seek to return familiar images and narratives to a new point of departure, one that allows us to look at them as if for the first time.

For me, history is a charged archive: unstable, dark, and contested yet at the same time brilliant, alive, full of beauty. I revive history and retell it; this is an attempt to make a correction to subjects, to time periods, and to icons that are considered controversial, complex, and disputed. The 100 Years Is Not Enough paintings in the exhibition draw heavily from the history of the art world. Monet’s Water Lilies is a big source of inspiration, but beyond that, they are resonant memories of Old Master paintings, memories that have fragmented and been translated into a more futuristic language.

Within the paintings exists a dark history of destruction, memory, and decay, yet alongside it there is also an intense emotional presence.

Becker: How does your new sculpture relate to the themes in the paintings?

There is something very emotional and mental in the connection between a human and an animal something that exists between desire and restraint. I want to challenge historical aesthetics and retell them. It’s important to me to give legitimacy to nudity, power, and personality; this is what we see in every museum in Europe, and these are the foundations of the art world, which unfortunately have gradually disappeared in favor of cheap, engineered politics.

Nudity comes from a place of tradition and from a desire to challenge social and museological conventions. I wanted to create a twist on decorative sculptures of nudity or animals such as leopards, horses, and deer that appear in many homes and spaces in America. But here in the sculpture called Lonely Girl and a Tiger I placed the tiger facing the woman: they look at one another and create tension. If you separate the leopard from the woman, they return to being ordinary sculptures that do not provoke much thought or conversation.

The sculpture is placed inside a room in the gallery, alongside the works on paper I created, as a continuation of styles and themes I have always loved in the history of art. Just as the paintings offer a twist on traditional landscape painting, the sculpture is also a twist on an entire genre of sculpture of nude women and animals, some domesticated, some wild.

I wanted to create a museum-like room within the gallery, which is why the walls were painted blue-gray, to create the right atmosphere. At first glance, everything looks normal and in order, but at a certain point it becomes something else. A different system of rules and morals emerges, challenging what we know and what we are accustomed to loving.

Becker: Your large paintings are dream-like. They transcend traditional landscape painting and present new ideas and new forms. What would you like viewers to experience in a room full of these paintings?

I would like the viewer to lose their sense of time and place. The works are not meant to be read as familiar or specific locations. They are a collage of hundreds of photographs of flowers, landscapes, and nature that I collect and work from, created out of memory rather than direct observation.

The works invite the viewer’s body first; the viewer becomes aware of their physical presence, and only afterward does thought begin. In the same way, there is movement and shifting within the works, because they reflect life itself. In front of the paintings, nothing is fixed.

I like to create a feeling of comfort that is actually an illusion, a soft entry point into something charged and heavy. I cannot ask the viewer what to experience, and I never truly concern myself with that. The entire technique of using chrome happened by accident; often, when you have no expectations, the best things happen.

Becker: How has your exploration of vanity and fragility evolved over your career?

These are motifs and themes that have interested me since the beginning of my career, both consciously and instinctively. I was drawn to the surface of the painting and to the effect it creates on the viewer as a form of power, alongside softness and fragility. I find it compelling that an image contains an internal conflict: something strong that becomes weak, or something weak becomes strong and overcomes it.

Over time, the contradiction became self-evident; it almost settled into a state of balance: control versus collapse.

Becker: What do you hope visitors feel as they move through this exhibition?

I’m not interested in something specific. In the end, everything is interpretation, an open, alternative world shaped by the personality and consciousness of each individual. What matters to me is the act of storytelling, and the way it is told. I think of it like a rock concert: the moment when the audience stops merely listening and begins to sing along with the performer. I want the works to become a space of resonance, where the viewer’s experiences are absorbed into the artwork and then returned to them, reflected across the surface of the canvases as an inseparable part of the work itself.